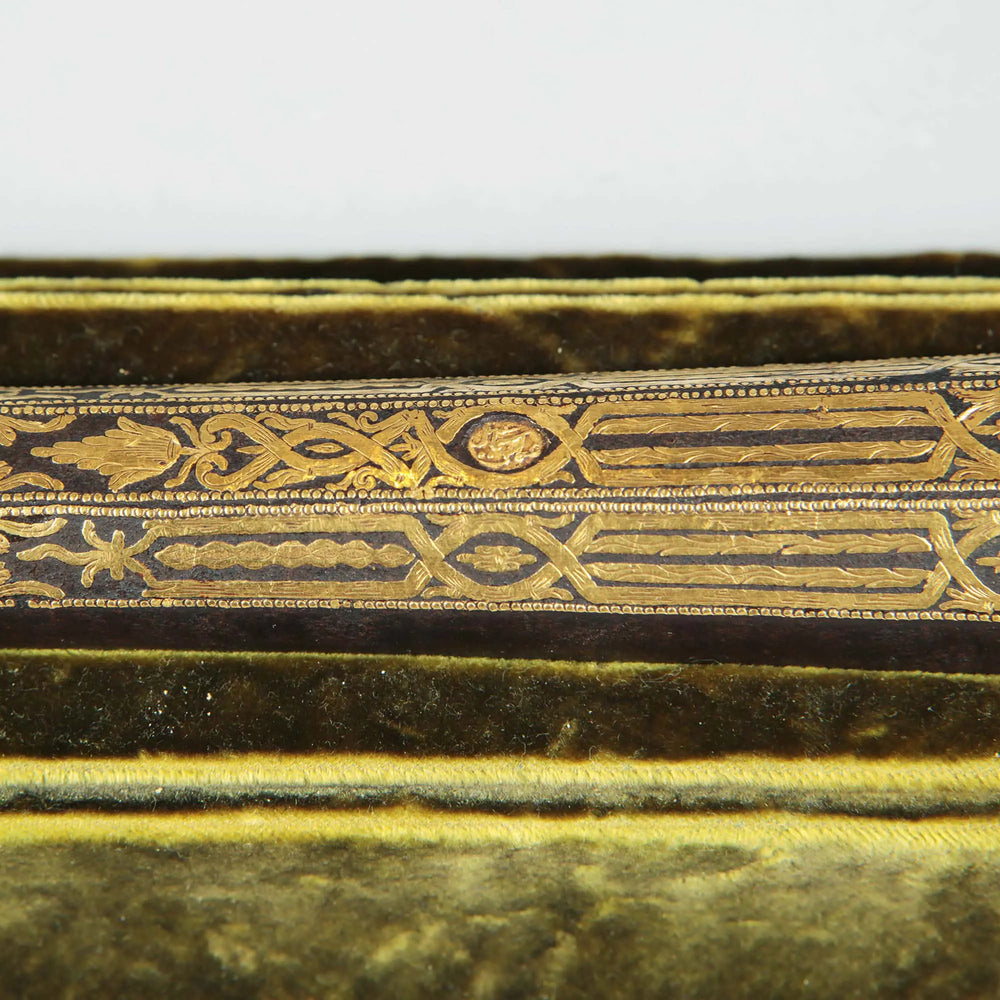

Damascus steel refers to a legendary type of steel historically used in the production of blades in the Middle East, especially between the 3rd and 17th centuries. Renowned for its distinctive wavy surface pattern and its combination of incredible hardness and flexibility, Damascus steel blades were feared and revered—said to be able to slice through lesser swords and even cut a silk scarf falling through the air.

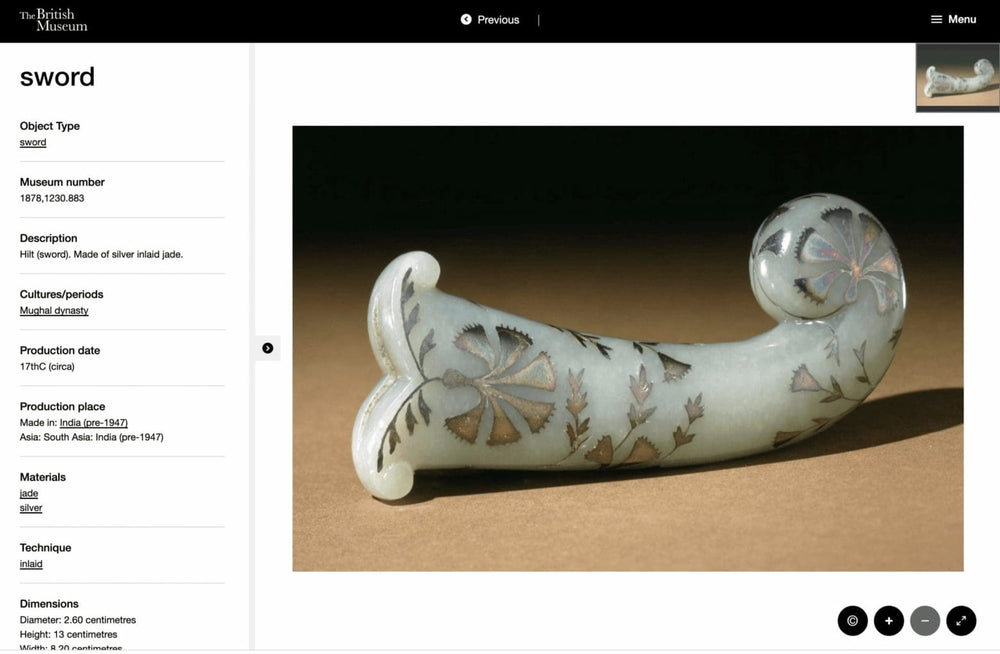

The original Damascus steel was made using wootz steel, a high-carbon alloy produced in ancient India and Sri Lanka as early as 300 BCE. This raw material was exported to the Middle East, where skilled smiths, particularly in Syria, forged it into weapons using a complex and largely lost process that involved controlled forging and repeated folding to develop the steel’s characteristic watery, mottled pattern. These blades were not only strong but unusually resilient—qualities essential for close combat and prized across cultures.

Despite its name, there is no conclusive evidence that this steel was produced in Damascus itself, though the city was a major trading hub for such weapons and likely lent its name to the style. The production methods of true historical Damascus steel faded by the 18th century, possibly due to the loss of the original wootz sources and changes in metallurgical knowledge. For centuries, the exact technique remained a mystery, giving rise to both legend and scientific fascination.

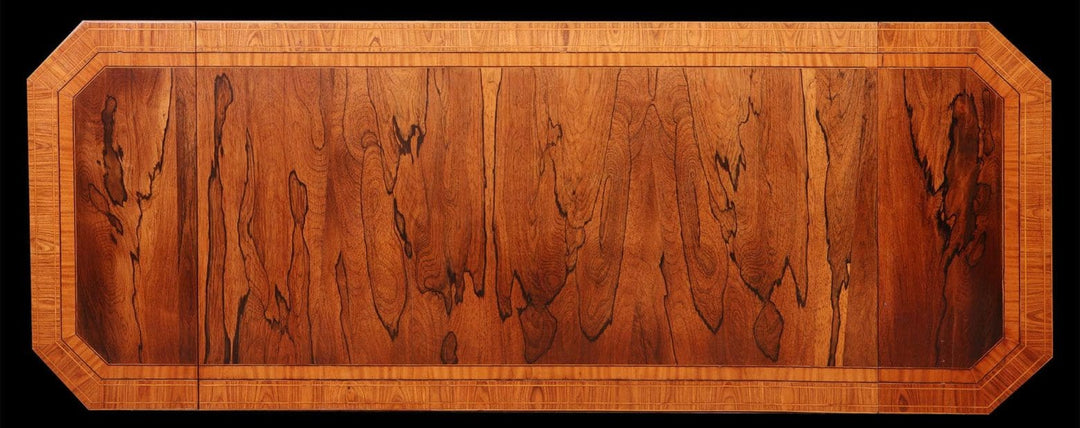

In modern times, pattern-welded Damascus steel—a different process that involves layering and forging multiple types of steel together—has revived the iconic look, though it does not exactly replicate the internal structure or properties of the original wootz-based steel. Contemporary bladesmiths continue to experiment with recreating the ancient material, blending artistry with metallurgy.

Today, both antique and modern Damascus steel items—particularly swords, daggers, and knives—are highly valued for their beauty, craftsmanship, and the enduring mystique of a material that once embodied the pinnacle of blade-making excellence.

Damascus steel refers to a legendary type of steel historically used in the production of blades in the Middle East, especially between the 3rd and 17th centuries. Renowned for its distinctive wavy surface pattern and its combination of incredible hardness and flexibility, Damascus steel blades were feared and revered—said to be able to slice through lesser swords and even cut a silk scarf falling through the air.

The original Damascus steel was made using wootz steel, a high-carbon alloy produced in ancient India and Sri Lanka as early as 300 BCE. This raw material was exported to the Middle East, where skilled smiths, particularly in Syria, forged it into weapons using a complex and largely lost process that involved controlled forging and repeated folding to develop the steel’s characteristic watery, mottled pattern. These blades were not only strong but unusually resilient—qualities essential for close combat and prized across cultures.

Despite its name, there is no conclusive evidence that this steel was produced in Damascus itself, though the city was a major trading hub for such weapons and likely lent its name to the style. The production methods of true historical Damascus steel faded by the 18th century, possibly due to the loss of the original wootz sources and changes in metallurgical knowledge. For centuries, the exact technique remained a mystery, giving rise to both legend and scientific fascination.

In modern times, pattern-welded Damascus steel—a different process that involves layering and forging multiple types of steel together—has revived the iconic look, though it does not exactly replicate the internal structure or properties of the original wootz-based steel. Contemporary bladesmiths continue to experiment with recreating the ancient material, blending artistry with metallurgy.

Today, both antique and modern Damascus steel items—particularly swords, daggers, and knives—are highly valued for their beauty, craftsmanship, and the enduring mystique of a material that once embodied the pinnacle of blade-making excellence.

Read More