Hardstone, encompassing agate, jasper, lapis lazuli, malachite, and other durable semi-precious stones, was one of the most celebrated materials of the 18th and 19th centuries. These stones were admired not only for their beauty and resilience, but also for the powerful geographical connections they embodied. To own an object of lapis from Afghanistan, malachite from the Urals, or agate from Idar-Oberstein was to hold in one’s hand a fragment of the wider world. This sense of material geography, inherited from the Renaissance Kunstkammer tradition, imbued hardstone works with an aura of worldly knowledge, discovery, and prestige.

Carvings and Sculptures

Carved hardstone vases, figurines, and animals revealed not just the artistry of the lapidary, but the wonder of the material’s distant source. Collectors prized them as much for their exotic provenance as for their form, recognising the stone itself as a token of nature’s artistry.

Mosaics and Inlays

Pietra dura panels and hardstone inlays often carried a coded language of geography: Florentine artisans worked malachite from Russia, chalcedony from India, and lapis from the East, transforming them into intricate designs that spoke of global trade routes and cultural exchange.

Jewellery and Accessories

In brooches, pendants, and rings, hardstones acted as miniature emissaries of place. A jasper cameo or an agate intaglio was not simply an ornament, but a link to the mountain or riverbed from which it was quarried.

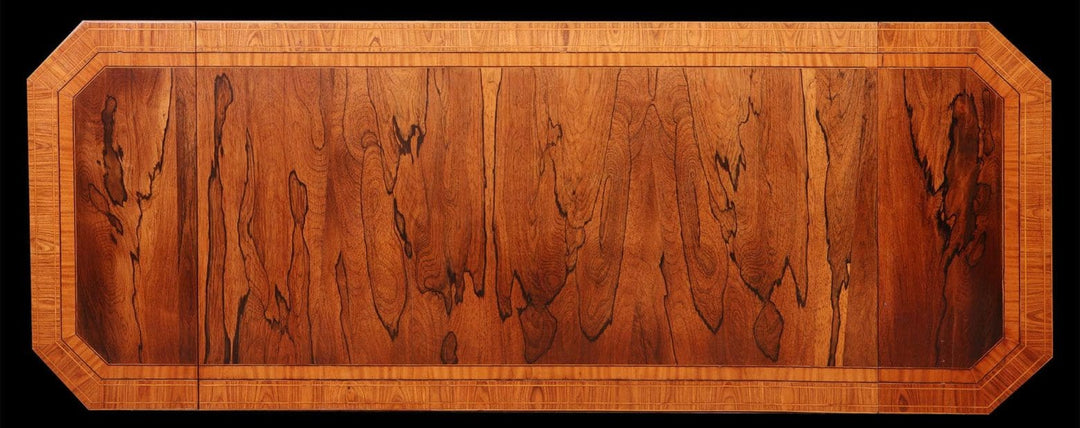

Tabletops and Decorative Furniture

Grand hardstone tabletops and plaques were centrepieces of salons and collections, their kaleidoscopic surfaces representing both the wealth of the patron and the global reach of the stone trade. For connoisseurs, each hue and vein carried meaning, signalling geological origin and cultural prestige.

Timepieces, Seals, and Religious Objects

Hardstone cases for clocks, engraved seals, and devotional items combined the symbolism of material permanence with the knowledge of worldly origins. Lapis altarpieces or malachite clock cases reinforced the idea that natural wonders could be channelled into both beauty and meaning.

A Collector’s Legacy

The fascination with hardstone in the 18th and 19th centuries lies not only in technical mastery, but in the cultural weight of its sources. Collectors valued these objects as repositories of knowledge: each piece of jasper or lapis was a fragment of the earth, tied to specific mountains, mines, and regions, transformed by human skill into something enduring. Today, antique hardstone works remain highly sought after — not merely as beautiful objects, but as historical witnesses to the era’s desire to catalogue, possess, and understand the world through its rarest and most remarkable materials.