The Palais-Royal, originally constructed for Cardinal Richelieu in the 17th century and later acquired by the Duke of Orléans in 1692, became a transformative centre of decorative arts, urban innovation, and sociability during the 18th and 19th centuries.

🏛️ Urban Development and Commercialisation

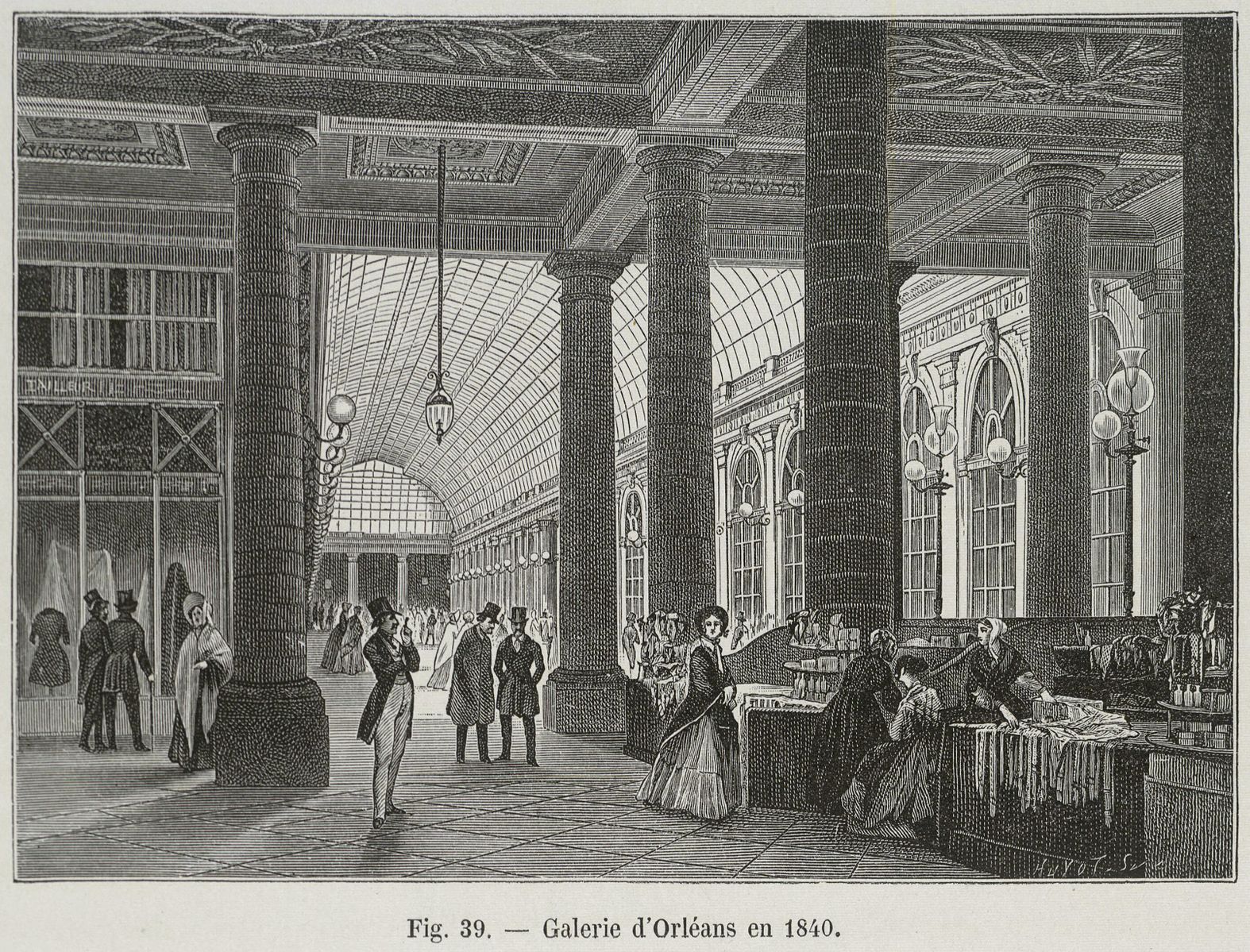

Between 1781 and 1784, Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, commissioned architect Victor Louis to construct six-storey apartment buildings with ground-floor colonnades surrounding three sides of the palace garden. These additions gave rise to new urban arteries—rue de Montpensier, rue de Beaujolais, and rue de Valois—and marked a shift toward commercial enterprise. By 1784, the arcades beneath the colonnades opened to the public, offering a dynamic mix of shops, cafés, salons, and services.

Over time, the Palais-Royal complex evolved into one of the earliest examples of a modern shopping arcade, blending leisure, commerce, and architecture. With 145 boutiques and establishments, it became the epicentre of Parisian social life, drawing aristocrats, bourgeois patrons, and the urban masses.

🛒 Luxury, Leisure, and Social Theatre

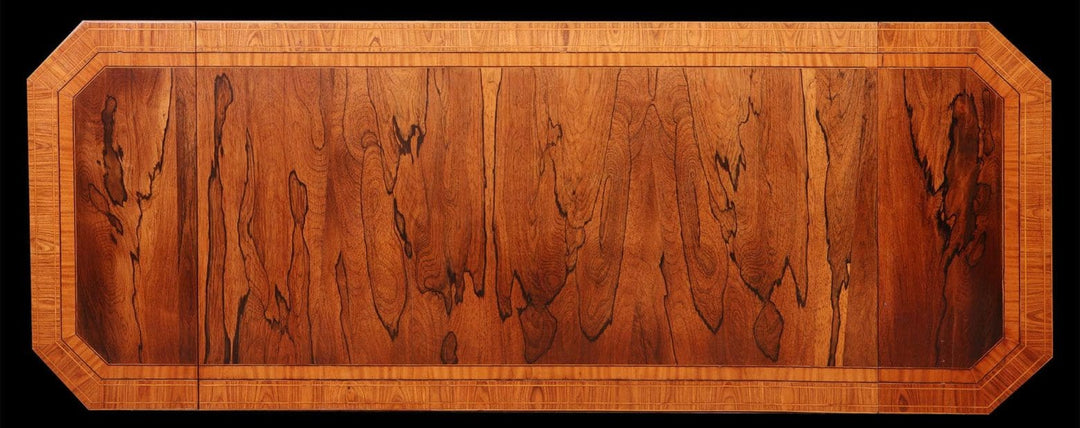

Retail spaces offered fine jewellery, furs, paintings, and furniture, often displayed in elongated glass windows designed to entice emerging middle-class shoppers to indulge in fantasy and promenade. The arcades were celebrated for their enclosed charm—sheltering patrons from the city’s noise and weather—and quickly became venues for seeing and being seen, regardless of price or provenance.

The atmosphere of the Palais-Royal combined:

- Cultured conversation in bookshops and salons

- Bohemian and libertine encounters, often associated with its more risqué offerings

- Political and philosophical discourse, including noted Freemasonic activity

As Abbé Delille famously observed:

Dans ce jardin on ne rencontre / Ni prés, ni bois, ni fruits, ni fleurs. / Et si l’on y dérègle ses mœurs, / Au moins on y règle sa montre.

“In this garden one encounters neither meadows, nor woods, nor fruits, nor flowers. And, if one upsets one’s morality, at least one may reset one’s watch.”

The noon cannon, installed in 1786 along the Paris meridian, added further intrigue—fired when sunlight struck a lens at midday. Though many of the more illicit elements have vanished, the cannon remains part of the arcades’ living tradition.

🎨 Decorative Arts and Cultural Patronage

The Duke of Orléans transformed the Palais-Royal into a hub for the decorative arts, commissioning ateliers and showrooms for furniture makers, textile designers, and craftsmen—including the celebrated André-Charles Boulle. Its interiors and gardens showcased elaborate fountains, statues, and formal plantings, reflecting the era’s investment in artistic display.

From the 1780s to 1837, the Palais-Royal was a centre of political intrigue, literary salons, and high society cafés—none more iconic than Le Grand Véfour, opened in 1784, still serving guests beneath its historic ceilings.

Throughout the 19th century, artists and designers continued to exhibit works at the Palais-Royal, affirming its status as a place where commerce, design, and Parisian identity interwove.

🏛️ Legacy

Today, the Palais-Royal remains a vital cultural landmark. Its arcades and gardens still reflect the layered history of a place where decorative arts, urban development, and social life converged—and where the art of promenade became inseparable from the art of display.