Napoleon and The Empire

Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, France’s greatest ruler and one of history’s finest military leaders, died almost 200 years ago, on 5 May 1821. In light of that approaching anniversary, art collectors and historians are once more turning their attention to the many social, political, and artistic achievements he instigated. Napoleon was not only a military genius but also a man of great intellect with a passion for the arts, commissioning the finest craftsmen of the day to create works that reflected both his power and aesthetic sensitivity. Over the years Nicholas Wells Antiques has acquired a number of works that illustrate Napoleon’s rise to fame and eventual downfall, as well as the types of artefacts he himself admired and inspired. Before referring to these directly, it is useful to outline who Napoleon was, why he became such an important figure, and how he shaped French — and indeed European — arts and history.

In his book Napoleon the Great, Andrew Roberts cites Sir Winston Churchill’s description of Bonaparte as “the greatest man of action born in Europe since Julius Caesar.” Napoleon himself greatly admired Caesar, whose regime and artistic style he sought to emulate when building his own empire. His beginnings, however, gave little hint of his future fame. Born into a minor noble family on 15 August 1769, on the French-owned island of Corsica, he was the first Corsican to study at the École Militaire in Paris. He proved himself an astute military strategist during the French Revolution, playing a pivotal role in suppressing a royalist uprising in Toulon in 1793 and another in Paris on 5 October 1795.

Promoted to general at the young age of 24, Napoleon quickly became regarded as France’s most popular commander. In 1802 he was appointed First Consul, and in 1804 crowned himself the first Emperor of France. Having successfully restored national stability after the Revolution, he imposed a series of reforms that united the country, many of which endure to this day. For instance, he introduced France’s first proper accounting system, dramatically reduced inflation, reformed the tax code, rebuilt much of Paris — including many of its present-day bridges, arches, and avenues — and re-established religious tolerance.

After conquering Egypt, Austria, Germany, Poland, and Spain, Napoleon’s army suffered catastrophic losses during the invasion of Russia in 1812. The following year he was defeated at Leipzig, forced to abdicate, and exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba. Having escaped and briefly regained power in France, he was finally defeated on 18 June 1815 at the Battle of Waterloo.

Napoleon’s rise to power came at a time when France’s political landscape was in turmoil, following the overthrow of Louis XVI and the ancien régime at the start of the French Revolution. A pivotal moment in that upheaval was the storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789, vividly captured in an intricate collage within this collection. Dating from c.1820, the work is composed of carefully rolled pieces of paper and is based on an original print by the lithographer Napoleon Thomas (b. 1810).

Exactly ten years after the storming of the Bastille, during the French campaign in Egypt, Napoleon defeated Mustafa Pasha’s Ottoman army at the Battle of Abukir. A magnificent mother-of-pearl flintlock rifle — identical to one formerly in our collection (now sold) — was seized from the Mamluk chieftain at this battle. During his Egyptian campaigns (1798–99), Napoleon was determined to record Egypt’s wonders. He travelled with a group of scholars and scientists, as well as the artist Baron Dominique-Vivant Denon. Denon’s subsequent published drawings sparked a renewed interest in the Egyptian taste during the Directoire and Empire periods.

Nevertheless, the dominant artistic influence of the time was rooted in classical Graeco-Roman art. This is exemplified by an imposing marble tazza with entwined serpentine handles by Lorenzo Bartolini (1777–1850), believed once to have stood in the sculpture gallery at Chatsworth House. Bartolini, one of Napoleon’s favoured sculptors, was appointed by the Emperor as professor of sculpture at the Italian Accademia di Belle Arti in Carrara, where he also headed the workshops. Supported by Napoleon’s sister Elisa, the Carrara marble workshops became a key centre for producing high-quality likenesses of the Emperor and his family. Many of these portraits were faithful copies or variations of original models by celebrated sculptors such as Canova and Antoine-Denis Chaudet (1763–1810), of whom our gallery holds a fine example.

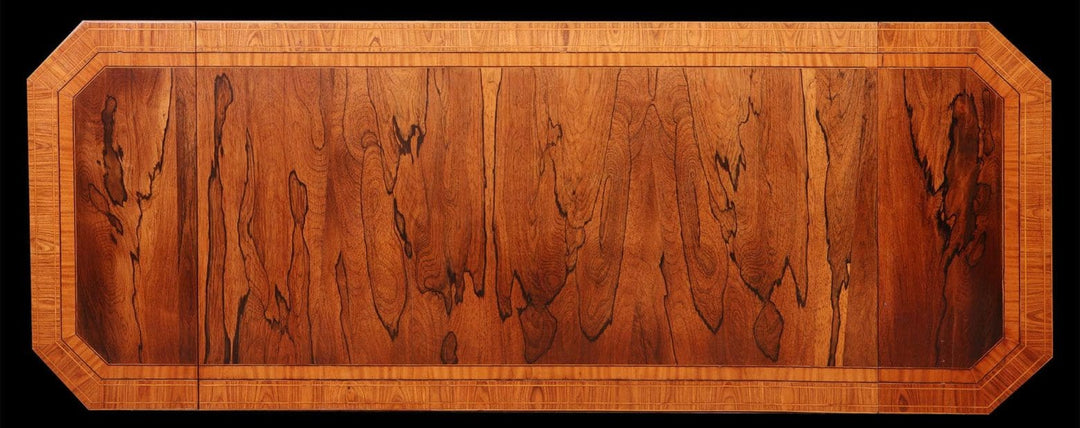

In addition to sculptors, Napoleon commissioned the leading painters, goldsmiths, bronziers, and ébénistes of his day, each producing works that embodied the grandeur of the Empire style. Among the finest examples is a superb ormolu-mounted burr elm commode and matching secrétaire à abattant, attributed to Bernard Molitor (1755–1833), which ranks among our most exciting recent discoveries.

Following France’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, Napoleon surrendered to the British, who escorted him aboard HMS Bellerophon to England. There he learned that he was to be exiled to the remote volcanic island of St Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean.

The final six years of his life were spent on St Helena, at the Longwood estate — first in an existing residence and later in New Longwood House, designed in the Grecian style by William Atkinson (c.1773–1839). This building is depicted on the front of an intricately carved Chinese ivory card case. The fact that the case was made in Canton, China, and after the Emperor’s death, is a striking reminder of how far Napoleon’s influence extended.

His legacy also inspired adaptations to earlier works of decorative art. For example, a North Italian walnut bureau cabinet from c.1750 was later fitted with ring handles, each bearing a profile of Bonaparte as a young general, reflecting the enduring fascination with his image and impact.

Most of the furniture, curtains, wall and floor coverings, as well as household utensils for New Longwood House on St Helena, were supplied by George Bullock (1782/3–1818), the acclaimed furniture maker and designer whose patrons included members of the British royal family. Among these was a French Grecian-style mahogany and ebony pedestal library desk, delivered by Bullock in 1816.

Interestingly, our gallery has recently acquired a Carlton House desk attributed to Bullock — a piece that stands alongside the finest examples of early nineteenth-century craftsmanship and reflects the exceptional quality for which he is renowned.

The reverse of the aforementioned card case is as significant as the front, as it portrays Napoleon’s tomb on St Helena. On 9 May 1821, four days after his death and in accordance with his wishes, France’s first Emperor was buried beside a glade of willow trees and a spring in the Sane Valley. He himself referred to it as the Vallée du Granium, owing to the profusion of geraniums he often passed when visiting Richard Torbett, a shopkeeper and Longwood’s main supplier, as well as Dr Kay, a physician with the East India Company.

Nineteen years later, Louis-Philippe of France obtained permission from Britain to exhume Napoleon’s body and return it to Paris for a burial befitting the nation’s hero. On 2 December 1840, more than a million people lined the streets of Paris to witness the funeral procession as it made its way to the Dôme des Invalides, where his remains still rest today beneath a monumental sarcophagus.

Such was Napoleon’s fame that, even after his death and second burial, his likeness continued to be reproduced. Among the many posthumous representations were a series of bronze statuettes by — and after — the French sculptor Émile Coriolan Hippolyte Guillemin (1841–1907), of which several fine examples survive.

We hope this brief introduction to Napoleon and the Empire period will inspire you to explore each of the items in greater detail. In doing so, one gains deeper insight into Napoleon’s life and the remarkable legacy he left behind. He was a man who established much of the modern French political, social, and judicial system; who transformed Paris with many of its enduring glories; who became the subject of more than 3,000 biographies; who inspired Beethoven; and who gave rise to the Empire style that continues to define a wealth of the decorative arts.

Leave a comment